Hindsight is 20-20. We all know this. And now that Ryan Braun has been suspended for his association in the Biogenesis scandal, it’s easy to to say that we overvalued Braun in our draft preparation. But let’s look back to what we knew in the preseason and use this as a learning opportunity to apply a lesson in weighted average probability and expected results.

What Did We Know?

News surfaced in early 2013 that Ryan Braun and numerous other players were associated with Biogenesis. Documents were obtained that showed an official link between the players and the clinic. There was speculation that the players involved could face suspensions during the season.

We didn’t know much more than this. Would players miss 50 games? 100 games? Would the suspensions come down during the 2013 season? Or after? Could MLB even uncover enough evidence to support suspensions?

What Could Happen?

For Braun, we could reasonably assume he’d be the target of a 100-game suspension. He was nearly the recipient of a 50-game suspension in the fall of 2012, but managed to avoid it on a technicality. So new evidence could push him from a first-time offender to a second-time offender (and a 100-game penalty).

Let’s Start A Basic Projection For Braun’s 2013 Season

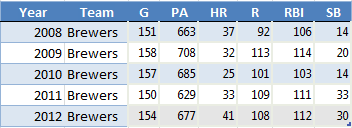

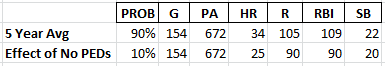

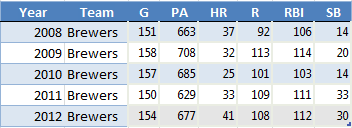

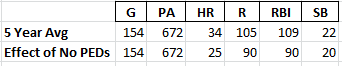

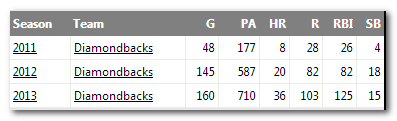

If we are to build a projection for Braun’s 2013 season, a reasonable place to start would be to look at career averages. Braun played a partial season in 2007 and played at least 150 games in 2008-2012. So let’s use these last five years of “full seasons” and figure out the average production as our baseline estimate:

These average to 154 games, 672 plate appearances, 34 home runs, 105 runs, 109 RBI, and 22 SB.

But What If This Isn’t An Average Season?

We know Braun was nearly caught as a PED user in 2012. So what if he was scared into stopping his use of PEDs? Can we build this into our estimate?

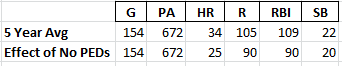

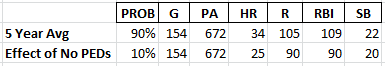

We don’t have any scientific data to understand the exact effect of PEDs. So let’s throw out a rough guess and say we think the effect of stopping the use of PEDs would slightly decrease his production. We’ll say his numbers would remain at 154 games and 672 plate appearances, but he drops to 25 HR, 90 R, 90 RBI, and 20 SB.

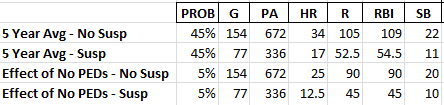

To summarize our two scenarios:

How Likely Are These Scenarios To Occur?

You might have your own beliefs about the likelihood of each, but for the sake of example let’s say we think Braun is 90% likely to have another year in line with his past five seasons and 10% likely to experience a year where the effect of no PEDs drags his performance down some.

And What If He Gets Suspended?

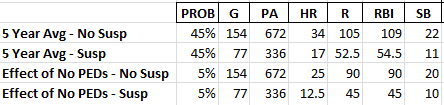

Again, for the sake of illustrating a simple example, assume a 50% chance Braun does not get suspended during the year and a 50% chance Braun misses half the season.

These 50-50 alternatives are subsets of our previous two scenarios. So the 90% chance Braun has another average year now becomes a 45% chance (90% * 50%) he has a career average year and does not get suspended and a 45% chance he has a career average year and does get suspended.

Likewise, the 10% chance he sees a drop in productivity due to coming off PEDs is split into a 5% bucket of not being suspended and a 5% bucket of being suspended.

Regardless of the scenarios we lay out, we must remain at 100% total probability for all the possible outcomes. Something has to happen. And with 45, 45, 5, and 5, we’re still at 100%.

Weighted Average Probability, Expected Results

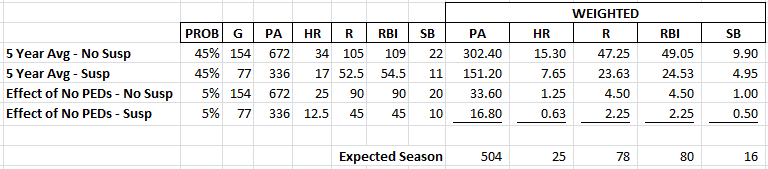

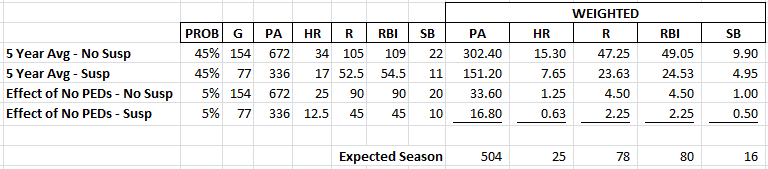

Once you have probabilities for each possible outcome, it’s easy to calculate the total expected result. We simply multiply the expected statistics for each scenario by the likelihood of that scenario. This is the “weighting”.

Look at the 5 Year Avg – No Suspension example. We have determined this scenario has a 45% chance of occurring. 45% multiplied by 672 plate appearances is 302.40. 45% multiplied by 34 home runs is 15.3. And so on.

Here are the weighted averages of all scenarios:

Our overall or actual expectation is the sum of each different weighted scenario. You can see this total at the bottom of the table above. After taking all possible scenarios and their probabilities into account, we estimated Braun for 25 HR, 78 R, 80 RBI, and 16 SB.

The Bigger Point

This approach of calculating weighted average probabilities can be used in many different scenarios. Do you think there’s a 25% chance Troy Tulowitzki plays a full season, a 50% chance he plays 120 games, and a 25% chance he plays 80 games? Do you think a rookie has a 25% chance of being called up in May, 25% in June, and 50% in July? Do you think there’s a 50% chance a player will bat leadoff during the year and a 50% chance he’ll bat 9th? Is there a 25% chance a rookie call-up will break onto the scene and be very productive, a 50% chance he’ll be an average player, and a 25% chance he’ll be sent back to the minors?

In any of these situations, calculate an estimated outcome and weight it using the probability of that outcome occurring.

Be Smart

Thanks for reading and continue to make smart choices.

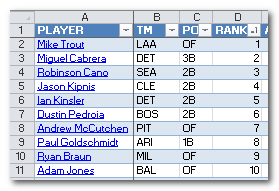

I recently finished my first rankings and projections for the 2014 season. And after I sent all the projection information into the little black box, it kicked out some really crazy looking results.

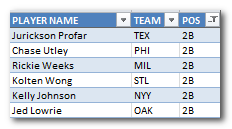

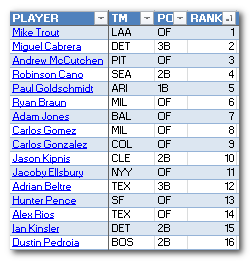

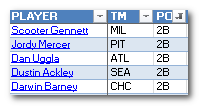

I recently finished my first rankings and projections for the 2014 season. And after I sent all the projection information into the little black box, it kicked out some really crazy looking results. I usually assume a standard rotisserie format when creating rankings, so for a 12-team league starting 2B, SS, and MI, I assume “replacement level” is right around the 17 – 21st ranked players at each position (12 2B starters plus about 6 more drafted to play MI). When I looked at this neighborhood of players, I came up with Scooter Gennett, Jordy Mercer, Dan Uggla, Dustin Ackley, and Darwin Barney as “Replacement Level”. A sad cast of characters. Darwin Barney? How did I not catch that?!?!

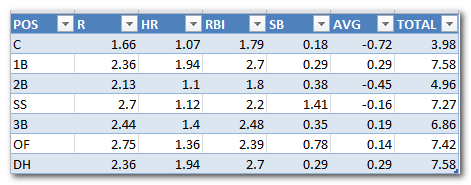

I usually assume a standard rotisserie format when creating rankings, so for a 12-team league starting 2B, SS, and MI, I assume “replacement level” is right around the 17 – 21st ranked players at each position (12 2B starters plus about 6 more drafted to play MI). When I looked at this neighborhood of players, I came up with Scooter Gennett, Jordy Mercer, Dan Uggla, Dustin Ackley, and Darwin Barney as “Replacement Level”. A sad cast of characters. Darwin Barney? How did I not catch that?!?! I then went the next step and included this 2B replacement level measurement in the replacement level table for all positions (see the table image above). It’s very clear that something is out of whack with 2B. With the exception of catcher, which we know lacks in offensive production (and the effect is worsened for two catcher leagues), all the other positions are within

I then went the next step and included this 2B replacement level measurement in the replacement level table for all positions (see the table image above). It’s very clear that something is out of whack with 2B. With the exception of catcher, which we know lacks in offensive production (and the effect is worsened for two catcher leagues), all the other positions are within